Globally, cities are expanding. By 2050, more than two-thirds of the population is expected to live in urban areas. This growth increases the demand for green spaces, prompting people to find creative ways to incorporate nture into a limited footprint. At the same time, awareness of native plants’ importance is on the rise. Driven by this need and curious about the outcomes, I took on the challenge of discovering to what extent native plants can successfully be grown in containers. With a mix of enthusiasm, trial and error, and plenty of sweat, I discovered what works best—often through unexpected lessons along the way.

Gardening in a major city

As an urban botanist based in Chicago, my encounters with wild plants are often limited to the same aggressive species pushing through sidewalk cracks or the predictable selection of ornamental plants in city gardens. While I appreciate the resilience of dandelions, the summer displays of impatiens, and even the fiery red of burning bushes in the fall, I know native plants can offer so much more. Determined to bring biodiversity to my own urban space, I transformed my small 5×10 balcony into a haven for native Illinois prairie species—an experiment driven by curiosity, a love for plants, and the challenge of growing them in pots year after year. With little guidance available on overwintering natives in containers, I had to select pots that could withstand Chicago’s harsh freeze-thaw cycles, experiment with different soil compositions, and carefully choose species that could thrive in a limited space.

Overwintering Results

Over 15 years, I’ve learned which native plants survive best in pots, which struggle, and which ones flourish beyond expectations. Species with fibrous roots or rhizomes, like certain asters and sedges, tend to overwinter well, while tap-rooted plants often struggle. I’ve also found that “nurse” plants, like Carex species, help stabilize soil and protect more delicate neighbors. Some of my standout performers include nodding onion (Allium cernuum, Zones 4–8), partridge pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata, Zones 3–9), and aromatic aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium, Zones 3–8), while overachievers like wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis, Zones 3–8) and stiff goldenrod (Oligoneuron rigidum, Zones 3–9) are great for beginners.

Overachievers:

I would recommend these plants for first-time growers. All were overall really robust and will thrive even with occasional neglect.

- Wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis, Zones 3–8)

- Lanceleaf coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata, Zones 4–9)

- Stiff goldenrod (Oligoneuron rigidum, Zones 3–9)

- Giant Solomon’s seal (Polygonatum commutatum, Zones 3–7)

- Heath aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides, Zones 3–10)

- New England aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae, Zones 4–8)

Favorite top performers:

In total, there are 23 plants that made my top-performers list. Here, I will keep the selection brief and highlight some of my favorites. Let me know in the comments if you’d like a deeper dive on this topic and my full list of recommendations.

- Partridge pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata, Zones 3–9) reseeds and attracts wonderful pollinators.

- Nodding onion (Allium cernuum, Zones 4–8) is a reliable performer. The city of Chicago gets its name from the Algonquin Indian name for this plant, chigagou, so Chicagoans can have a little extra pride growing this native.

- Spotted beebalm (Monarda punctata, Zones 3–8) self-seeds easily and produces a wonderful display. It also attracts some amazing wasps.

- Sand phlox (Phlox bifida, Zones 4–8) and wild blue phlox (P. divaricata, Zones 3–8) are two of many phloxes that are amazing and worth the effort.

- Aromatic aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium, Zones 3–8) is not too aggressive and has amazing fall color.

Favorite good performers:

This list is longer—31 native plants altogether. These are all wonderful, but there were small issues that left them off the top-performers list. Either they did not do well every year or were a messier plant to deal with, but that does not mean they aren’t worth buying and potting up. Here were my favorites from that list:

- Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum, Zones 4–8) is almost a top performer but is messy and big. However, pollinators love it, and it also self-seeds nicely.

- Canada anemone (Anemone canadensis, Zones 3–8) is a bit aggressive but produces a nice display.

- Harebell (Campanula rotundifolia, Zones 3–6) is a little messy but so beautiful.

- Prairie clover (Dalea spp., Zones 3–8) can create such great displays but does not always overwinter well.

- Fringed loosestrife (Lysimachia ciliata, Zones 3–9) was a surprise. The color and floral display are wonderful, but it can also be aggressive.

- Starry campion (Silene stellata, Zones 5–8) has fantastic flowers, but it did struggle at times.

- Large-flowered bellwort (Uvularia grandiflora, Zones 4–9) is a personal favorite that lived many years but did not always flower.

Conclusion

Despite setbacks, this ongoing experiment has proven that native plants can thrive in containers, providing vital habitat for pollinators and adding beauty to even the smallest urban spaces. My hope is that by sharing my success, more city dwellers will be inspired to bring native plants into their own lives, creating richer, more sustainable urban landscapes.

Find more information on growing native plants in the Midwest:

Discuss this article or ask gardening questions with a regional gardening expert on the Gardening Answers forum.

And for more Midwest regional reports, click here.

Jeremie Fant is the Director of Conservation at the Chicago Botanic Garden in Glencoe, Illinois. He has been testing different native plants in containers for over 15 years.

Photos: Jeremie Fant

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Niteangel Natural Wooden Insect Hotel, Garden Insect House for Ladybugs, lacewings, Butterfly, Bee, Bug

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

The insect nest box provide a safe environment where garden creatures can shelter, hibernate and lay their eggs, the insect house can also keep insects from entering your warm room. The insect hotel makes it easy to find and observe fascinating creatures. the butterfly, bees and ladybugs can use this product as habitat. Dry wood and Bamboo can be home to many insects such as ladybirds and lacewings which eat aphids and help keep your plants pest-free. the insect hotel improve the growth of plants in your yard by attracting beneficial insects. The iron design on the top can keep the insect house from rainwater. Let the insect house have a longer useful life and make the insects more comfortable. If you only have a balcony or yard, the hanging garden shelter is ideal as it provides a choice of suitable habitats in a small area.

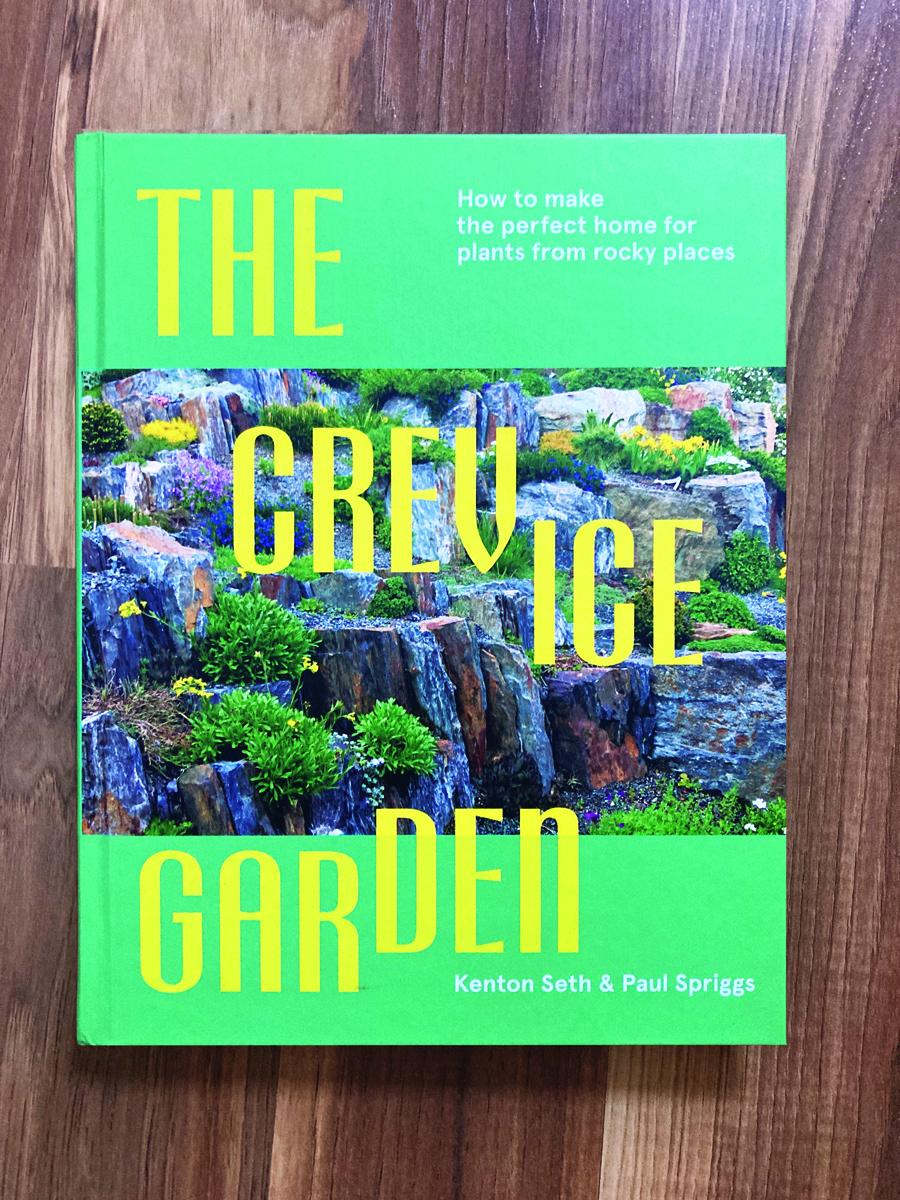

The Crevice Garden: How to make the perfect home for plants from rocky places

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A crevice garden replicates the environmental conditions of mountain tops, deserts, coastlines, and other exposed or rocky places on earth. These striking garden features provide perfect conditions for the plants native to these far-off places, bringing the cultivation of these precious gems within everybody’s reach.

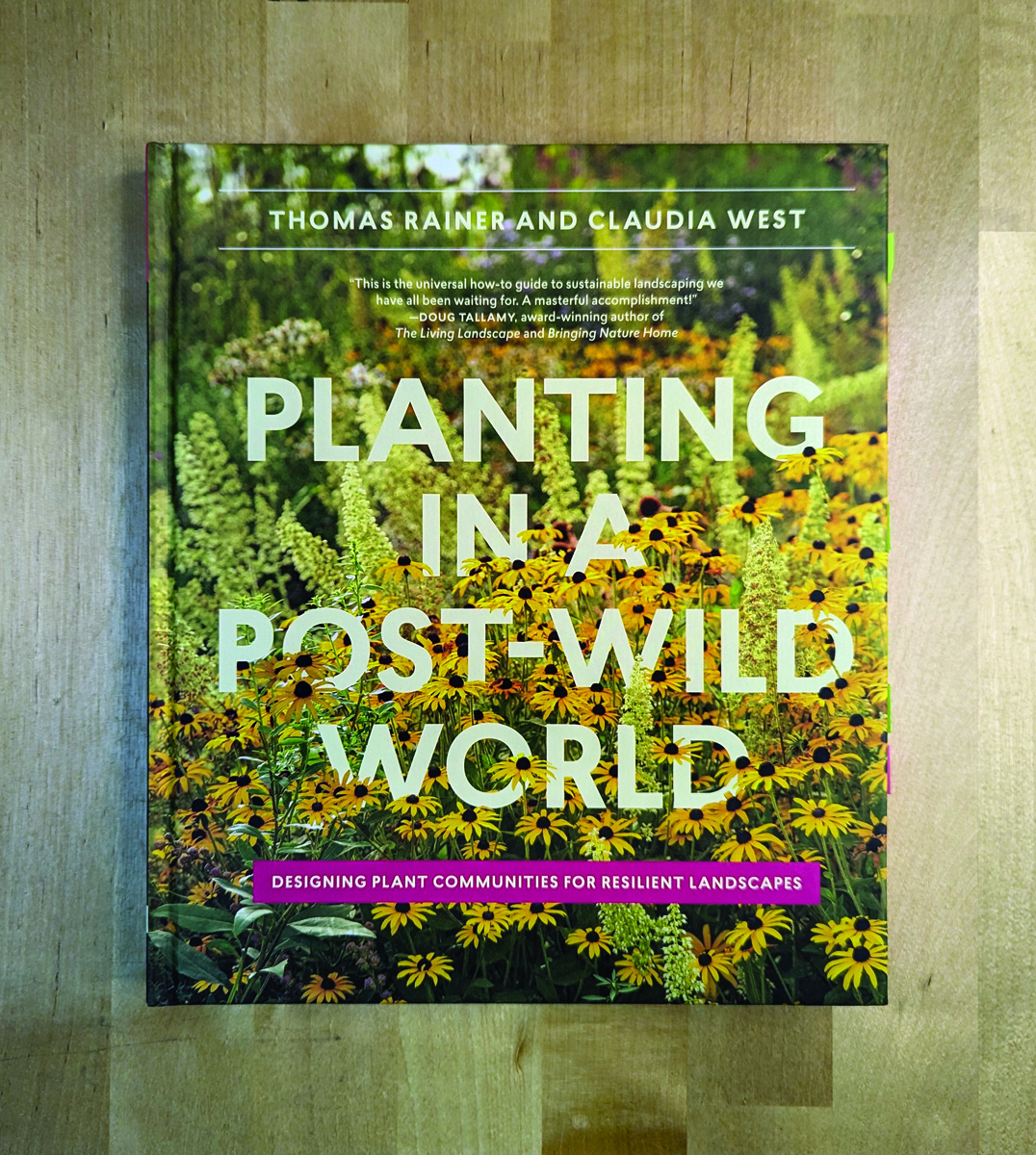

Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Featuring gorgeous photography and advice for landscapers, Planting in a Post-Wild World by Thomas Rainer and Claudia West is dedicated to the idea of a new nature—a hybrid of both the wild and the cultivated—that can nourish in our cities and suburbs.